Dirac-Delta Function

These things are the most annoying as fuck functions you will see actually exist in mathematics. Basically, a dirac-delta function, labelled δ(x), is defined as follows: $$ \tag{☆}\delta(x)= \begin{cases} 0 & \quad x \neq 0 \newline \infty & \quad x = 0 \end{cases} $$

This is its most basic function definition, but it also has to satisfy these conditions: $$ \int_{-\infty}^\infty \delta(x)~dx = 1 $$

Now because we said the function was 0 everywhere except when x=0, this can just be generalized to $$ \tag{☆}\int_{-\alpha}^\alpha \delta(x)~dx=1\quad $$

or even $$ \int_{\alpha-\varepsilon}^{\alpha+\varepsilon}\delta(x-\alpha)~dx=1 $$

as long as α is a positive real number greater than some ε > 0. Now if we think about this intuitively, we know that integrals just capture the area under the curve. When x=0, we can imagine a area under the infinite spike as a rectangle with a width that’s really close to 0 and a height that’s really close to infinity. The area of this rectangle is just (base × height), so we get that $0 \times \infty = 1$. Okay holy shit we just broke all of math. This wasn’t supposed to happen…

Just kidding we can’t really say that this is true because of technicalities of infinitesimals, but the integral still holds true… so ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Definitions

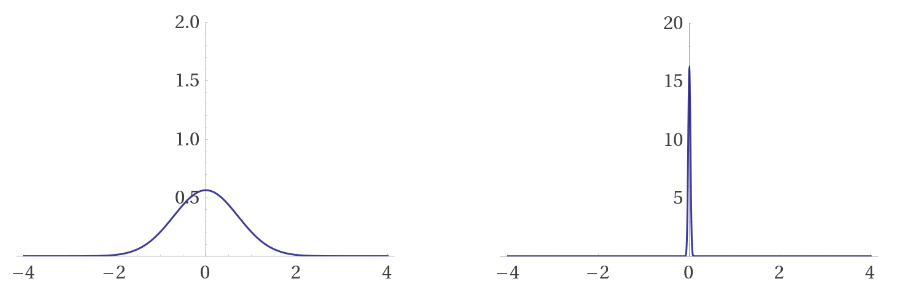

One of the more janky definitions of a delta function includes using $$ \delta(x)=\lim_{\varepsilon\to 0} \frac{1}{\varepsilon\sqrt\pi}e^{-{x^2}/{\varepsilon^2}} $$

where the function inside the limit looks quite similar to a gaussian distribution. It only becomes apparent as a delta function when we shrink that constant ε towards 0.

The graph on the left shows the function at ε = 1, while the graph on the right shows the function at ε = 0.035. Note the scale of both graphs. Clearly, when we let ε approach 0, the function will just be 0 everywhere until the spike to infinity at x=0.

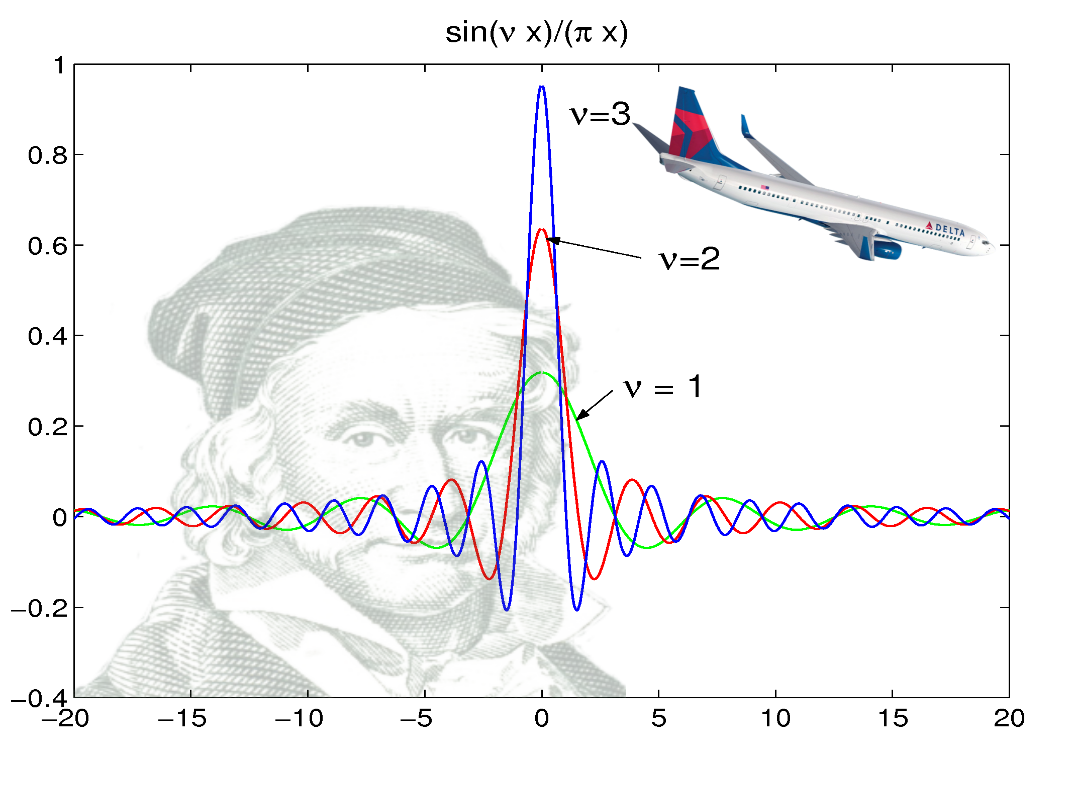

There other such definitions of the delta function, such as $$ \delta(x)=\lim_{\varepsilon\to 0} \frac{1}{\pi}\frac{\varepsilon}{\varepsilon^2+x^2}=\lim_{a\to \infty} \frac{1}{\pi}\frac{\sin(ax)}{x} $$

It’s the same deal here. Note that we need to have the factor of 1/π on the outside in order for it to be the delta function, even though we cannot tell the behavior of the function at infinity. Why? I have no fucking clue, but you need it.

Properties

Using the last definition from the previous section, we can derive one of the simplest properties of the delta function. We will try and find: $$ \int_{-\infty}^\infty \delta(x)f(x)~dx=\lim_{a\to\infty}\frac{1}{\pi}\int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\sin(ax)}{x}f(x)~dx $$

for some continuous function f(x). Let’s use a substitution of t = ax, and thus dt = a dx. $$ =\color{red}{\lim_{a\to\infty}}\frac{1}{\pi}\int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\sin(t)}{t}\color{red}{f\left(\frac{t}{a}\right)}~dt $$

We can now bring the limit inside the integral and recognize that the only term with a in it is the f(t/a), and then we know that $\lim_{a\to\infty} \frac{t}{a} = 0$: $$ \begin{align} &=\frac{1}{\pi}\int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\sin(t)}{t}\cdot\color{red}{\lim_{a\to\infty}f\left(\frac{t}{a}\right)}~dt\newline &=\frac{\color{red}{f(0)}}{\pi}\int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\sin(t)}{t}~dt\newline &=f(0). \end{align} $$

Since $\int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\sin(t)}{t}~dt=\pi$. Thus, we obtain the property: $$ \tag{☆☆}\int_{-\infty}^\infty \delta(x)f(x)~dx=f(0) $$

Another similar property can be derived with basically the same method: $$ \tag{☆}\int_{-\infty}^\infty \delta(x)f(x-a)~dx=f(a) $$

Now there are some properties dealing with just the delta function itself: $$ \delta(ax)=\frac{1}{|a|}\delta(x) $$

This one is not at all important because when will you ever use this, like seriously. $$ \delta(f(x))=\sum_i \frac{1}{|f’(x_i)|}\delta(x-x_i) $$ where each xi is a zero of f(x) and we are summing across all zeroes of f(x). This also leads into our last integral property: $$ \tag{☆☆}\int_{-\infty}^\infty\delta(f(x))g(x)~dx=\sum_i \frac{g(x_i)}{|f’(x_i)|} $$ Now this property is probably the most important out of all of them. To college professors, at least.

Extra Shit

The integral of the delta function is “properly” defined to be $$ \int_\infty^x \delta(x)=H(x) $$

where H(x) is the heaviside step function: $$ H(x)\equiv \begin{cases} 1 & \quad x > 0 \newline 0 & \quad x < 0 \end{cases} $$

and is just left either undefined at zero, or for more intensive purposes, 1/2. Now this makes sense because the area under the delta function is 0 until the spike at x=0, and then it becomes 1 for the rest of function until positive infinity.

If you’re asking me why it’s called a heaviside step function, it’s just because some idiot mathematician decided to snag the name of a “unit step function”. The guy’s name is Oliver Heaviside. But it should really be Oliver Clothesoff because that’s probably what he was better off doing :c

Anyways. The derivative of the delta function is, well, a bit more complicated. It’s apparently defined to be: $$ \delta’(x)=(\delta*u)(x) $$

where we’re taking the convolution of the delta function, δ, and whatever a “unit doublet” is, u. But this is not important, so we’re going to skip talking about the rest of this.

There is, however, one important thing involving the derivative of delta functions, which is $$ \int_{-\infty}^\infty f(x)\delta’(x)~dx = -f’(0) $$

This follows from a step of integration by parts: $$ \int_{-\infty}^\infty f(x)\delta’(x)~dx = \underbrace{[f(x)\delta(x)]{-\infty}^\infty}{=~0}-\int_{-\infty}^\infty f’(x)\delta(x)~dx $$

The left expression is 0 since δ(x) is 0 everywhere (even at x=infinity) except for x=0, and the right expression is just similar to the first double-starred equation above.